Our Borderless, Infinite Reality

On why different ways of seeing are vital

An essay prompted by a question from David Perell's Write of Passage

IN THE SWEEP OF HISTORY, it’s often the small encounters that capture the essence of entire generations.

One such small encounter occurred in the streets of Paris, on the boulevard Raspail.

The year is 1914, and war has just been declared between all the powers of the earth. The streets are still quiet, seemingly unaware of the looming disaster and doom that will soon ravage Europe.

Gertrude Stein, the expatriate American writer, collector and ‘den mother’ of artists and bohemians, is walking along the boulevard with her Spanish friend Pablo Picasso. They are coming home from dinner, and in the moonlight they see a small convoy approaching.

As the first truck drives by them, both Stein and Picasso notice something different.

The sides of the truck are splashed unevenly with different colors of paint; shades of green, olive, sage, emerald, with brown hues crisscrossed amongst them.

At first they freeze, and then realization washes over them. It is a camouflaged truck.

They had heard of camouflage but this was the first time they were seeing it. Picasso is amazed when he looks at it. He exclaims, “Yes it is we who made it,” pointing to the camouflage, “that is cubism”.

Recounting this small incident in her biography of Picasso1, Gertrude Stein captures the entire zeitgeist of the shifting world around her. In the dynamic patches of camouflage she sees a complex world:

“the composition [of this war] was not a composition in which there was one man in the center surrounded by a lot of other men but a composition that had neither a beginning nor an end, a composition of which one corner was as important as another corner”.

In fact, this was the composition of Cubism.

If you look at a Cubist painting, you’ll be overwhelmed by the fragmented and abstract vision that presents itself. This art movement originated in the early 20th century and revolutionized European painting and sculpture. You could easily decry it as yet another modernist movement, but a Cubist aesthetic is exactly what’s needed to understand our particularly fragmented world.

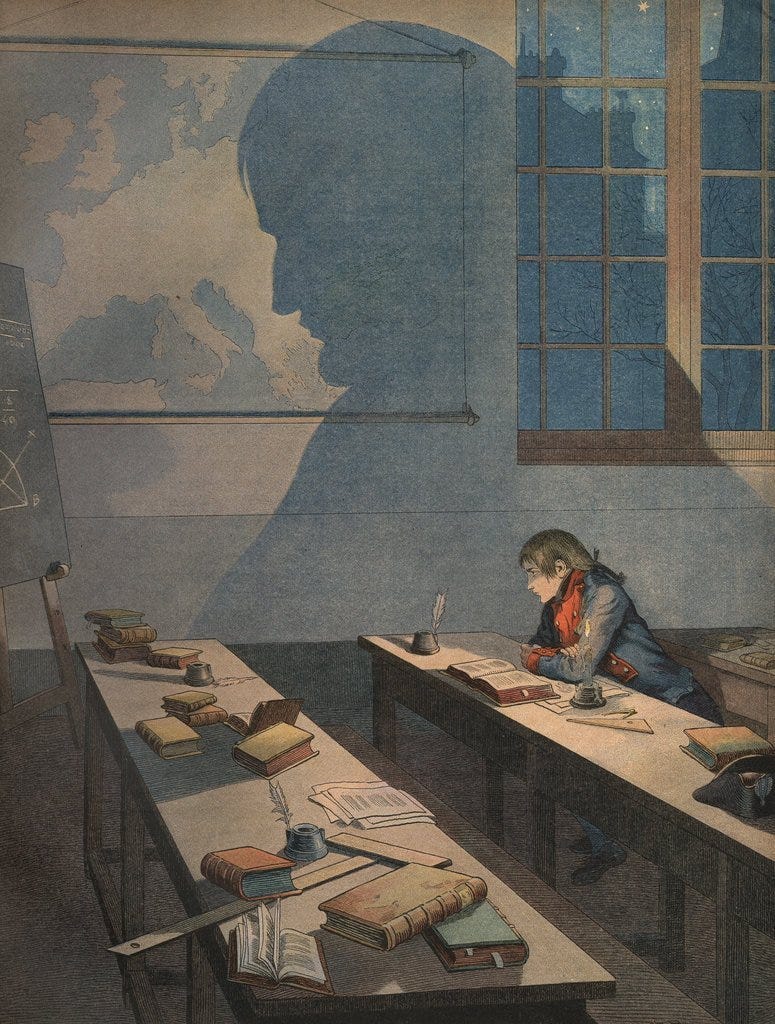

Today, adopting a static model of reality. Old paintings and lithographic prints (like Napoléon à Brienne) capture their subjects really well, but fail to capture the zeitgeist and complex dynamics at play in their society at the time. There’s a lack of chaos that seems almost jarring.

Napoléon à Brienne (circa 1780) a lithographic print by Jacques Marie Gaston

Napoléon à Brienne (circa 1780) a lithographic print by Jacques Marie Gaston

Picasso's Guernica (1937)

Picasso's Guernica (1937)

We need a new approach. An approach that is inspired by Cubism, which brings in different views of subjects together in a single picture. One that is full of varying angles and superpositions.

We need to adopt a view that is sensitive to the shifting dynamics of situations, to the interconnectedness of things. This requires mapping out different nodes in our head, knowing how one node can tug at the heart of the network, and affect all other nodes in turn.

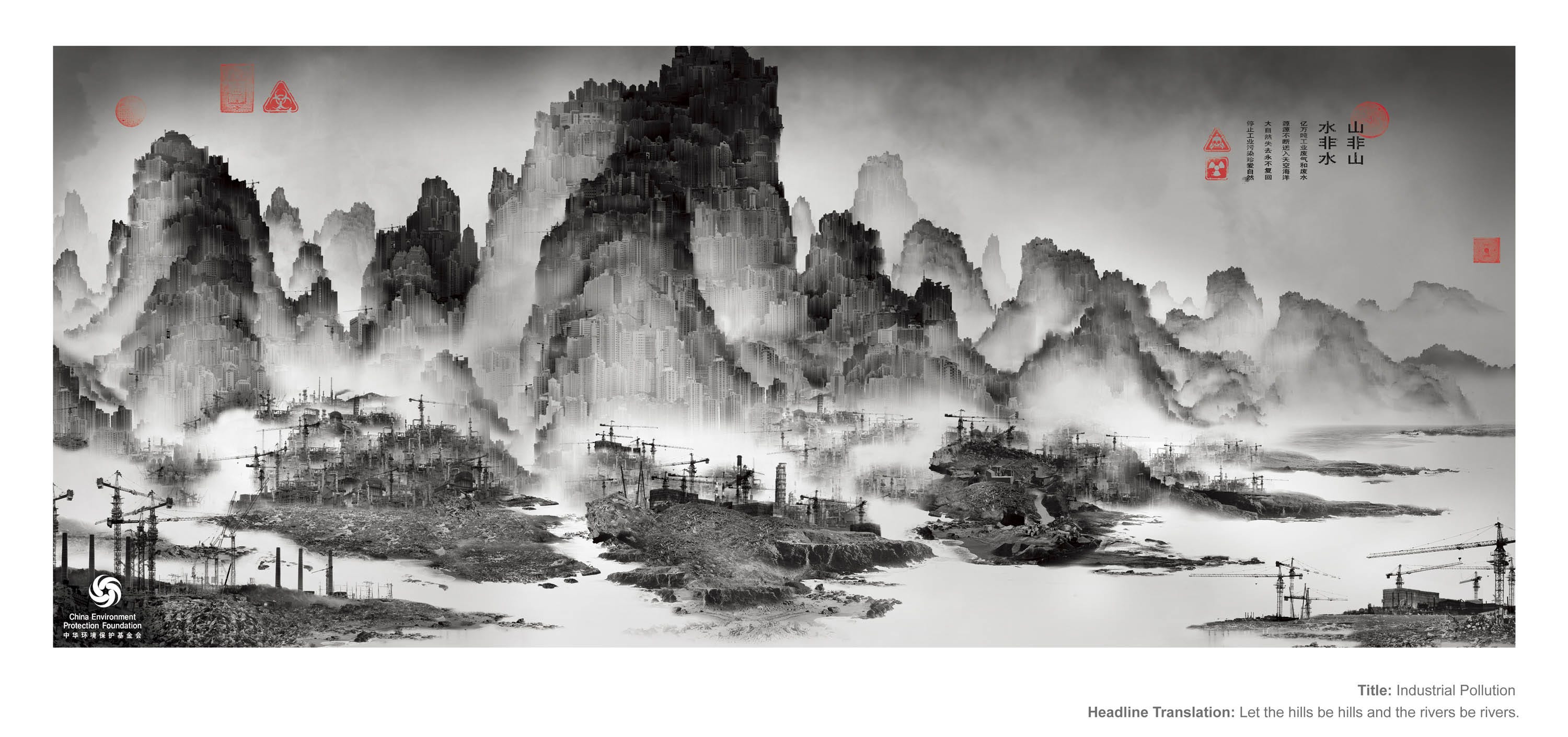

All this can be overwhelming. After all, the scale of the world is massive, and it may seem like you are trapped in a Chinese Shan shui painting2. That’s quite the point - Shan Shui landscape art - in its depiction of winding rivers, ethereal mists, and looming mountains - aims to capture the vital breath of the world in all its complexity.

Past Meets Present: Shan Shui Environmental Art | Ekostories

Past Meets Present: Shan Shui Environmental Art | Ekostories

As the landscape of our world has started to resemble that of a Cubist canvas: crisscrossed supply chains, complex networks, and its scope resembles the Shan Shui paintings of old, the only way to win is to map it all out.

To find patterns3. To go deep and broad.

As Stein said, each man in the center is surrounded by other men. The same could be said of institutions, or even ideas.

Understand the system, and we might just have a chance.